by Nina

|

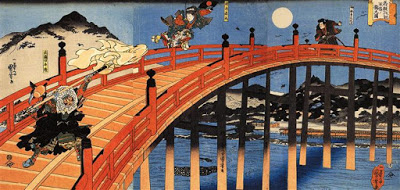

| The moonlight fight between Yoshitsune and Benkei on the Gojobashi by Kuniyoshi |

“Humans and chimpanzees are the only primates known to frequently engage in warfare. If this type of aggressive behavior was common during their evolution, then the fight-or-flight response likely played a critical role in adapting to the threat of deadly conflicts. “—Science Daily

Typically when you read about stress and the fight-or-flight response, the writer explains to you that in our hunter-gatherer ancestors this response prepared them to deal with large predators (tigers or wooly mammoths or whatever) and other dangers in their outside environment. Then they talk about how in modern times (in the first world?) we typically don’t face those types of dangers but our fight-or-flight response is still triggered by less serious “dangers,” such as traffic jams and deadlines at work. But it turns out that humans and chimpanzees have a more “active” fight-or-flight response than other primates. So there may be another (more depressing) explanation for why we are still experiencing such strong fight-or-flight responses on a regular basis.

In Ramped up fight-or-flight response points to history of warfare for humans and chimps Science Daily reported on a paper in PLOS Selection on the regulation of sympathetic nervous activity in humans and chimpanzees. In this study, scientists analyzed the genomes, transcriptomes, and epigenomes of humans and chimpanzees and compared them to those of other primates to see whether “inter-group aggression” had an effect on the evolution on humans and chimpanzees that caused them to have more active fight-or-flight responses. In other words, because human and chimpanzees (unlike macaques and bonobos) tend to fight amongst themselves, their genes could reflect that they evolved to be on the high alert from danger coming from their own species. And the scientists did find, in fact, that humans and chimpanzees acquired “genetic and accompanying epigenetic changes that decrease ADRA2C expression, thus increasing signaling for the fight-or-flight response.” So our strong fight-or-flight response is genetically built in as a result of the human tendency to fight with each other and ultimately to conduct warfare.

After you get over the depressing thought that humans evolved to be better at fighting each other, it does explain some things. In the hunter-gatherer age, it was not large predators that really stressed us out, but it was other human beings. And guess who we are still surrounded by on a daily basis?

To me this makes it more important than ever for us to use yoga’s stress management tools (see The Relaxation Response and Yoga and Stress Management for When You’re Stressed) on a regular basis to moderate the effects of stressful encounters with other people. (I swear there are people out there getting angry lately just because I’m in a crosswalk and they have to wait for me to finish crossing the street.) It also makes me think about what I’ve read recently in Edwin Bryant’s The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali about how ahimsa (non-violence) is the most important yama and the “root” of all the other yamas.

“Acccording to Vyasa, the goal of the other yamas is to achieve ahimsa and enhance it, and he quotes an unidentified verse stating that one continues to undertake more and more vows and austerities for the sole purpose of purifying ahimsa.” —Edwin Bryant

Obviously the ancient yogis observed that one of our main problems as a species is a tendency not only toward taking violent actions but also toward having violent thoughts about other people. And taking violent actions and having violent thoughts not only interferes with our peace of mind (the fight-or-flight response interferes with our ability to think clearly—see Stress and Your Thought-Behavior Repertoire) but also causes bad relationships, thus perpetuating violence.

But even though we evolved to have a strong fight-or-flight response, we also have the capacity to observe that about ourselves and to intentionally cultivate ahimsa (non-violence).

Sutra 1.33 In relationships, the mind becomes purified by cultivating feelings of friendliness towards those who are happy, compassion for those who are suffering, goodwill towards those who are virtuous, and indifference or neutrality towards those we perceive as wicked or evil. —translated by Edwin Bryant

For information on how to cultivate ahimsa, see Victor’s post Daya: A Yoga Practice of Compassion from yesterday (perfect timing!), my post Removing Negative Feelings, and Ram’s post Non-Violence (Ahimsa) and Healthy Aging.

Follow Yoga for Healthy Aging on Facebook ° To order Yoga for Healthy Aging: A Guide to Lifelong Well-Being, go to Amazon, Shambhala, Indie Bound or your local bookstore.

This explains exactly why I hate being around large groups of human beings and my anxiety level automatically goes up when in large gatherings…when human animals are in large groups their egos and violent tendencies are much more likely to be expressed in a negative, destructive manner.

I think Jiddhu Krishnamurti summed it up perfectly…"it is no measure of health to be well adjusted to a profoundly sick society"