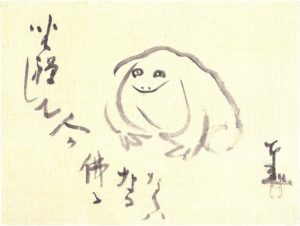

Meditating Frog by Sendai

by Nina

Our ability to plan for the future is one of the qualities that made us so successful as a species. During the hunter-gatherer era, concern about the future helped us stockpile food for the winter and eventually led to the development of agriculture. And we also made plans to avoid repeating dangerous mistakes, for example, by organizing a hunting party to take down a large animal instead of hunting solo. And the powerful urge to plan is as beneficial to us for our survival in the modern world as it was in more primitive times. For example, we benefit from stocking up on supplies and boarding up windows in advance of a big storm and from saving money for retirement. Then because planning is so important to us, we become very attached to the plans we make and to the outcomes we’re hoping for.

But as you know, many of our plans don’t work out because circumstances that our plans depend on can change. And sometimes changes make things so uncertain that we can’t even make plans! This can be very stressful for us because letting go of plans we’ve made can be painful and not being able to make plans for the future is very frustrating!

In addition, our orientation toward the future may even cause us to overlook what’s happening in the present. For example, I knew someone who was so focused on the milestones they had mapped out for the future—the list was literally on the refrigerator—that they failed to see how unhappy they were making their partner until it was too late.

So there are many times when this urge to plan isn’t helpful and prevents you from facing the reality of actually what’s going on in the present.

Another natural urge that we evolved with that prevents us from being present is our tendency to revisit the past. Revisiting the past can be very beneficial in that it allows us to learn from our previous experiences. It prevents us from repeating the same mistakes and encourages us to repeat experiences that were beneficial for us. But this too isn’t always helpful. Spending too much time revisiting good experiences in past can make us unable to appreciate the good things in the present because we’re always comparing the present with the past. And constantly revisiting bad experiences can create painful feelings of depression, guilt, regret, or shame.

In Tantra Illuminated Christopher Wallis describes the four forms of grasping that he says prevent us from “immersing ourselves” in the present moment:

“In the past we grasp toward positive memories, which is called nostalgic reverie, and we grasp after painful memories in the form of guilt and regret. We grasp future imaginary possibilities, which is called fantasy, and future negative possibilities, which is called worry or anxiety.”

On the other hand, if you’re anchored in the present, when something changes you won’t be comparing the present with the past and feeling the loss or blaming yourself or others for how things turned out. And you won’t be fantasizing or wishing that the future will bring the solutions to all your problems or miraculously set things back to the way they were in the past. Wallis says that when we let go of the four forms of grasping, “past and future become part of our present and experience the fullness of the present, which has much more to offer us that the mind could ever imagine.”

During the extreme fire season in 2020 California, I found it more challenging than ever to stay present. My mind raced into the future: Was there going to be a serious fire season every year from now on? Would we be able to continue living in California, where I previously thought we’d spend the rest of our lives? I caught myself worrying about the future pretty quickly and reminded myself of my “Don’t panic too soon” motto. I came up that motto back in the 1990s when I was working in the high-pressure environment of a small software startup company—the company would fail if we didn’t get our product out on time—and I was in charge of the complete set of documentation! And that motto has helped me ever since. I also used my yoga practice during the extreme fire season to stay calm and be present with what was happening rather than panicking too soon. (Yes, “Don’t panic too soon” is a play on the cover of The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy.)

My friend Melitta Rorty said something similar. When she notices that she is stressed about the future or ruminating about the past, she brings/drags herself into the present just by saying to herself, “This present moment is perfect, there is nothing wrong here,” and in less than a minute, this leads her to a calmer state. But I think that the little phrases Melitta and I use to remind ourselves to be present only work because she and I have been practicing yoga for decades. Through our practices, we have learned to bring ourselves back to the present, over and over, when we notice that our minds are drifting off into the future or the past.

That’s why in my book Yoga for Times of Change, I’m dedicated a chapter to pranayama and meditation. These are both are powerful practices for training you to be present because of the concentration they require.

Pranayama trains you to be present because it is the practice of conscious breathing. Because we normally breathe without thinking about it, intentionally changing the way you breathe, especially for an extended period of time, takes a lot of concentration! So breath practices are a good way to yoke your body and mind to the present moment. Focusing on your internal sensations will settle your mind, and being present will take your mind off regrets about the past and worries about the future.

And although there are many different forms of meditation (see All Good but Not Equivalent: Meditation Types), all forms of meditation train you to be present. Whatever you choose to meditate on—your breath, a mantra, the sensations in your body, the sounds in the room—you are focusing on something that is taking place in the here and now. And when you notice your mind wandering, you bring it back to the present, again and again. Although you’re not present the entire time you meditate, repeating this process of bringing your mind back to your object of meditation trains you to notice when you’re not present in your everyday life and to then return your focus to the present.

Practicing either pranayama or meditation—or both—can help you become more present in your everyday life because you will develop the habit of noticing when your mind is wandering. And the more you practice returning your focus to the present, the stronger your habit will become, both in the yoga room and in your life.

For more information on both pranayama and meditation, you can search on those topics on the blog (we have a ton of info on both!) or read the chapter in my book Yoga for Times of Change called “Being Present.”

• Follow Yoga for Healthy Aging on Facebook and follow Nina on Instagram • Order Yoga for Times of Change here and purchase the companion videos here • Order Yoga for Healthy Aging: A Guide to Lifelong Well-Being here.

Leave A Comment