by Leslie Howard![]()

After fifteen years of teaching yoga for pelvic health, I’m so frustrated that doctors and other medical professionals still continue to prescribe Kegel exercises as the solution to every pelvic floor problem they encounter in their practices, from pelvic pain to incontinence and prolapsed uteruses.

Unfortunately, this recommendation that “Kegeling” is a cure-all for all pelvic floor conditions proves the saying that if all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail. If the only tool you have to address pelvic health problems is squeezing everything tight, then loose is all you perceive. But in fact many pelvic problems are caused by tightness, not looseness.

Now there is certainly a role for Kegel exercises for pelvic health. But it’s just one tool, which cannot, and should not, be used across the board. It may even be harmful when used inappropriately. You wouldn’t use the hammer to fix the delicate heirloom tea set you inherited from your grandma, would you? Likewise, Kegels can be harmful for pelvic pain, some forms of incontinence, and—believe it or not—some prolapses.

This is why I strongly believe that we need to understand our pelvic conditions and understand which tools are best for us. Let’s start by looking at what Kegels are and how they should and should not be practiced. I will then provide an overview of which conditions they are helpful for and which they are not helpful for.

What Are Kegels?

Kegel [key-guhl] verb—squeezing everything from the navel to the knees and hoping for the best, as defined by Leslie Howard

When I ask my students to define Kegel exercises, they most commonly describe it as performing a contraction that stops the urine flow. There is a vague but general consensus that this exercise involves squeezing “down there.” But what exactly is being squeezed and for what purpose? That’s where things start getting murky.

The exercise was developed by Dr. Arnold M. Kegel, a Los Angeles–area obstetrician and gynecologist. He wanted to develop a remedy for a problem he had noticed in many of his patients: laxity of the vaginal walls and incontinence after childbirth. So he had his patients practice vaginal contractions both pre- and post-childbirth. In 1948, he devised the “Kegel perineometer,” a pelvic-muscle sensor to measure the efficacy of these voluntary muscle contractions. The perineometer was essentially a biofeedback machine. It used a vaginal sensor and an air-pressure balloon that measured the air pressure inside the vagina and verified that the Kegel exercise was being performed correctly.

Over the decades, however, Dr. Kegel’s exercise for strengthening the vaginal walls has become the “go-to” remedy for any problem of the female pelvis. Indiscriminately squeeze “down there” for any and all pelvic floor issues, whether it’s appropriate or not.

This has led to two different problems. The first has to do with the way many people perform Kegel exercises. And the second has to do with when these exercises are appropriate and when they are not.

How To Perform Kegel Exercises—And How Not to Perform Them

To understand why many people practice Kegel exercises incorrectly, let’s go back to the description of Kegels being the action of stopping urine flow. This definition is problematic on several levels. If we are told to find the muscles that cut off urine flow, we are more than likely to think of just one section of the pelvic floor. That’s because what actually stops urine flow is the urethral sphincter, located toward the front of the pelvic floor. This sets up a neural pathway in our brain that exercising the pelvic floor muscles is something that takes place more in the front, which may or may not be where your problem is. So if you’ve dutifully done your “Kegels” thinking they are about stopping your urine stream but haven’t seen any results, it may be because you are exercising the incorrect area for you. Don’t worry, you are not alone.

This lack of knowledge about how to perform Kegels correctly often extends to the healthcare professionals who prescribe the exercises. A patient may be told that the best way to practice a Kegel is to stop the urine stream at midpoint. Please don’t do that! That can lead to urine retention. Proper Kegeling takes time, effort, and a nuanced understanding—it’s not something that can be easily understood from the brochure that the nurse hands you on the way out of the exam room. Just finding the pelvic floor muscles, unlike much larger muscle groups like hamstrings or gluteus, requires subtle awareness and training.

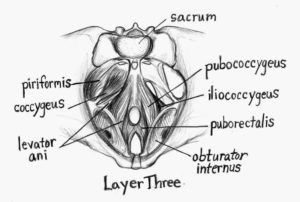

So what is correct Kegeling? It engages the pubococcygeous (PC) muscle. The PC is part of the levator ani, and the levator ani muscle group is part of the pelvic diaphragm. In turn, the pelvic diaphragm is part of the larger set of pelvic muscles. Get the picture? Doing a proper Kegel engages only one component of a large team of muscles. Just like in team sports, it won’t help if you focus on one all-star muscle, because for optimal performance you need the whole team working in a coordinated way.

There is nothing wrong with practicing vaginal wall contractions if and when it’s suitable. I thank Dr. Kegel for his insights and early dedication to women’s pelvic floor health. In his day, he was a pioneer in the field.

What are Kegels Suitable And Not Suitable For?

You may ask, should I be doing Kegels at all? And the answer is: it depends. If you have been diagnosed with lax muscles of your pelvic floor (called hypotonic), Kegels can help to strengthen and tone the pelvic floor muscles. If you are having stress incontinence that is not accompanied by constipation, doing Kegels may be helpful. If you are a new mom and delivered vaginally, feel less sensation or diminished orgasm, or experiencing what I call “varts” (air that goes into the vagina in inverted poses like Downward-Facing Dog and Headstand and make a sound like passing gas when you come down), Kegels might be the answer to your issues.

However, having taught pelvic floor awareness for so long what I know is many people do not have strong awareness in this area. My pelvic floor physical therapists tell me that one in three patients are bearing down when they think they are lifting up! And most students are not aware that the two sides of your pelvic floor can be completely different, like your stronger and weaker arm. Hence, Kegels can work for certain conditions, but you need to develop more nuance than just squeezing everything and hoping for the best.

In addition, while Kegels can be beneficial, yoga has been shown to be especially helpful. The advantage yoga provides over Kegels is that yoga cultivates inner awareness and works on lengthening, strengthening, and relaxing the whole body. Supporting your pelvis and spine with integration of your body parts is your best medicine.

I have some proof to support this argument! I’ve actually helped design two studies yoga for pelvic health at the University of California, San Francisco. The pelvic pain study pilot showed a 42% decrease in symptoms in six weeks and a second study is under way. The incontinence study showed a 70% improvement in symptoms in six weeks. The pilot study was published here Specialized Yoga Program Could Help Women with Urinary Incontinence. We got a HUGE grant from National Institutes of Health to replicate it. That study has been underway for the last three years and we hope to have results within a year of the big study.

And when should you avoid Kegels entirely? Doing Kegels for conditions that are caused by tightness rather than looseness can be counterproductive and can make symptoms worse. Some of these conditions include:

- urge incontinence

- some pelvic pain issues such as vulvodynia or vaginismus that are caused by tightness rather than looseness

- vestibulititis

- lichen sclerosus

- sciatica

- IBS

For these types of conditions, working on releasing tightness is what is going to helpful.

Conclusion

I hope this overview has given you a better understanding of the role that Kegel exercises can play in pelvic health. In the weeks to come, I’ll be writing about how we can use yoga poses and the way we practice them to either supplement the Kegel exercises for more optimal pelvic health or, in the case of conditions where tightness is actually the problem, to use yoga to lengthen and strengthen.

In the meantime, if you’d like to learn more about my approach to yoga for pelvic health, you can find my book Pelvic Liberation at www.lesliehowardyoga.com or Amazon.com. I also have two workshops coming soon that you might be interested in “Yoga and the Pelvic Floor” and “Yoga for Pelvic, Hip, and Low Back Pain.” See willowstreetyoga.com for further information and to register.

Leslie Howard is an Oakland-based yoga teacher, specializing in all things pelvic. She leads workshops and trainings nationally and has written a book about caring for the female pelvis, Pelvic Liberation. She is a regular presenter for the Yoga Journal conferences and a regular contributor to Yoga Journal magazine. Her own struggles with healing her hips and pelvis led her to intense study of the anatomy, physiology, cultural messaging, history, and energetics of this rich area of the body. Her teaching is informed by over 3500 hours of yoga study with senior Iyengar yoga teachers. She considers Ramanand Patel her most important influence and mentor. She has designed two very successful studies for UCSF on how to use yoga to alleviate incontinence and pelvic pain.

NOTE FROM THE EDTIOR FOR EMAIL SUBSCRIBERS: This post was accidentally published before it was complete and that caused it to go out in the email to the list of subscribers. Now you’re getting it a second time. This version is the final one so ignore the previous email. Sorry about that!

Follow Yoga for Healthy Aging on Facebook ° To order Yoga for Healthy Aging: A Guide to Lifelong Well-Being, go to Amazon, Shambhala, Indie Bound or your local bookstore.

Leave A Comment