by Richard Rosen

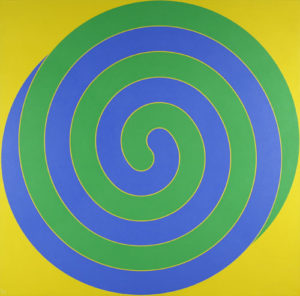

Earth Day by Edna Andrade

“The practice of yoga brings us face-to-face with the extraordinary complexity

of our own being.” —Sri Aurobindo

Back in 1891, after nearly thirty years of research, an American astronomer named Seth Carlo Chandler confirmed what Isaac Newton had predicted about 200 years earlier, which is that there’s a “slight displacement” in Earth’s rotation. What does that mean? It means our planet doesn’t spin exactly straight around its axis. There seems to be some disagreement among scientists regarding the displacement’s main contributing factors, though it’s generally accepted that Earth’s shape plays some part.

We imagine Earth is a perfect sphere, like a baseball, but, like all rapidly rotating celestial bodies, including stars, the North and South poles are flattened by the force of that rotation; in other words, Earth would make a terrible baseball because it’s not a perfect sphere, its diameter at the equator is about 30 miles greater than its diameter at the poles. We’re all living on what’s called an oblate spheroid, and like an unbalanced spinning top, as Newton anticipated, and Chandler proved, the Earth wobbles.

It’s no surprise the “slight displacement” is now called the Chandler Wobble.

Now before we move on to yoga, we should look into the word “wobble” itself. I searched through at least a dozen dictionaries and discovered that wobbling has a bad rep. It’s a sure sign that something’s irregular, staggering, clumsy, trembling, and vacillating, not to mention all the “un-like” things it is, like unbalanced, unsteady, uncertain, and uneven. I didn’t unearth even a single kind word about wobble, not even a hint it could be useful or fun.

Yoga Sutra has a good definition of wobbling. Yoga Sutra’s claim to fame is that it’s the first-ever presentation of a complete yoga system, usually called either Classical or Raja Yoga. It was compiled sometime in the fourth or fifth century CE by a mysterious figure that tradition names Patanjali. One dictionary definition for wobble is “fluctuate.” Wobble is a word at the heart of Patanjali’s teaching about yoga, which he defines as the “restriction of the fluctuations of consciousness.” or, to paraphrase, we practice yoga to “stop all our wobblings.”

Without going into detail, Patanjali sees wobbling as an inherent quality of material nature, which isn’t just trees and dogs and rocks. He believes our consciousness (citta) is also a material process, composed of the same stuff as all that other stuff. Only citta stuff is subtler. How does it work? When our eyes fixate on a chair, for example, our citta wobbles to match its shape and other qualities, and we say, “Oh, that’s a chair.” But it’s not our citta that ultimately makes that determination. It just thinks it does, since its “graspy” ego is always standing by on alert to pull everything into its orbit. Be that as it may, like all matter, our consciousness (citta) is entirely nescient. Put another way—human consciousness isn’t conscious.

The way it works is that citta and its sensors, ears, eyes, tongue, etc., receive information from both outside and “inside” worlds (perceptions from the former, thoughts, feelings, memories, etc. from the latter) and pass both along to our True Self, the actual knower. Since it has no substance, our Self never wobbles, but ironically unless it has some connection to something that does wobble, it has nothing to know and nothing to know with. This is what the English mystic-poet William Blake meant when he said (and I paraphrase), “I see through my eyes, not with them.”

The problem is that the wobbling is much more alluring than the static Self, and we’re irresistibly drawn to it, like a moth to a flame-and you know how that usually turns out. This misconception, treating the wobbling self as if it were the True Self, leaves us with a powerful but inexplicable feeling of loss and so burdens our life with an unremitting existential sorrow . Patanjali’s solution then is the only one that’s feasible is to end the sorrow and be ourselves as we truly are by severing our association with wobbling nature, which includes our body.

Patanjali’s solution takes the form of the well-known eight-limb (ashta anga) practice. After some preliminary work to drain away as much of his emotion as possible, the experienced practitioner trains himself, with the help of the guru, to sit stock-still for hours on end, barely breathing, or not breathing at all (inhales and exhales are perceived as wobbles). With his senses withdrawn from the outside world and re-directed “inward” to his citta, he now seals himself in a self-created cocoon. Nothing gets in, and nothing out.

Inside the cocoon, he gradually learns to focus all his attention on a single point, the wobble of which grows subtler and subtler over time, until one glorious day the last wobble drops away. He then emerges from his cocoon, not as a beautiful, fluttery butterfly–that world to him no longer exists–but as an immaterial, quality-less monad, bound to remain in blissful, self-absorbed, un-wobbling isolation for eternity. Just to be clear, the views expressed in this part of the story are not the author’s but are entirely those of Patanjali and his commentators.

As an Iyengar-trained teacher/practitioner, I spent my yoga babyhood studying the Yoga Sutra, which is the Iyengar school’s traditional guidebook. Since that school places a heavy emphasis on asana performance I learned very early on in my teacher training that, according to Patanjali, not to mention Mr. Iyengar, wobbling in yoga was everything the dictionaries said it was, and that went double in an asana. For an Iyengar student’s asana, nothing less than “steady and comfortable” was acceptable, and even then, there was always some question. After all, “today’s maximum is tomorrow’s minimum.”

So I pushed myself, and was driven by my teachers, to “strengthen that back leg,” or “reach up through the heels,” or “firm the outer arms inward.” The wobbling slowly diminished as I felt I was “rounding” myself not so much toward fulfilling the concept of steady and comfortable as I had no illusions about my overall ability in asana, but at least toward a bearable level of wobbliness.

Then in 2002, after 22 years of practice, the wobbles returned in a brand-new shape, grinning madly, and this time they were here to stay. The first sign something was changing was a constant numbness in my toes. Next came the occasional shuffling gait and the bouts with depression. I was diagnosed with Parkinson’s Disease (PD). PD makes you weaker, stiffer, and wobbly. After all the thousands of hours I’d spent getting myself strong, flexible, and evenly keeled, I came to the conclusion that the universe has a very wry sense of humor.

My practice changed considerably (as did my life), and with it, my understanding of wobbling. Slowly but surely the wobbles crept back into my practice and my life. I had two choices: I could punch and counterpunch with every “steady and comfortable,” anti-wobbly, boxing move I learned over the years, or I could try something radically new, and just accept them.

The wobbles didn’t have my best interests in mind, I was sure of that, but I could see the futility in trying to knock them out. I reluctantly welcomed the new wobbles as being as natural to me as they are to Earth (and now, at 72, my belly, like Earth’s diameter, is growing more oblate every day).

It appears that after 18 years, the strategy is working fairly well. There’s no doubt the condition is advancing, but at a rate my PD doctor deems “ridiculously, miraculously slow.” He always insists it’s “your yoga” that we have to thank, but I’m not so sure. It could be that, or my new leaf approach, or I’m just plain lucky. On the bright side, the wobbling has inspired my creativity with a wide variety of supportive props, blocks, straps, chairs, sandbags, wedges, blankets, you know, everything a yoga teacher needs to change a light bulb. It’s supplied me with extra tools to help other celestial bodies, my students, with similar conditions. Maybe someday I’ll come up with a word, not exactly extolling wobbles, but at least something that gives them some credit for being of some use under some limited conditions.

But I also must admit the wobbling has encouraged me to be more conscious of myself. I’ve found that a Patanjali-like focus on the wobbles when they’re acting up serves to calm them down, and I don’t even need a cocoon. They’ve also made me more aware of my surroundings, shuffling down a city street within full PD is akin to navigating an especially devious obstacle course, cracks, tree roots, and curbs are hiding everywhere to trip me up. Not being a perfect sphere then is a mixed bag, but I always remember what my favorite yogi, Yogi Berra, once wisely opined: “If the world was perfect, it wouldn’t be.”

This is an excerpt from Embrace your Wobbles: Wisdom from the yoga mat, edited by Priscilla Shumway. Available here from Amazon.

Follow Yoga for Healthy Aging on Facebook ° To order Yoga for Healthy Aging: A Guide to Lifelong Well-Being, go to Amazon, Shambhala, Indie Bound or your local bookstore.

Thanks Richard. It was the best of times, it was the wobbliest of times. Miss you