by Ram

Sometime back I wrote about my personal experience with Ehlers-Danos Syndrome (EDS), a condition that is associated with loose, hypermobile joints that have a greater than normal range and degree of movement. People with Ehlers-Danos Syndrome can dislocate their joints easily and joint pains are very common and for many years my yoga practice always ended with severe pain in the joints and limbs, and blood clots in several areas. Fortunately, after several years of practice and with lot of modifications, my asana practice has now metamorphosed into a stage where the focus is to achieve a higher state of positive experience, contentment, and a sense of accomplishment. Instead of going deeply into the pose right away or twisting recklessly, my goal is to strengthen all my vulnerable joints. In the process I was limiting the depth of the range of movement, but I was at the same time experiencing far less pain. Despite all these precautions, I continue to experience periodic episodes of widespread pain in the joints and limbs.

A couple of years ago, I was in the middle of my yoga practice with my left knee bent and the heel snugged into my left groin, right leg wide apart, bending deeply down over my right leg in Parivrtta Janu Sirsasana (Revolved Head-to-Knee Pose) when I heard it—a popping sound in my right lower back. I untwisted my torso and, without coming to upright, swept it midway between the legs and gradually lifted myself to an upright position. As I came up, I noticed a dull ache over my sacrum but I ignored it. As days passed and my yoga practice continued, I realized that the dull ache intensified and I experienced pain that radiated from the hip socket and all the way down the outside of the right leg. The pain was excruciating in twists and forward bends.

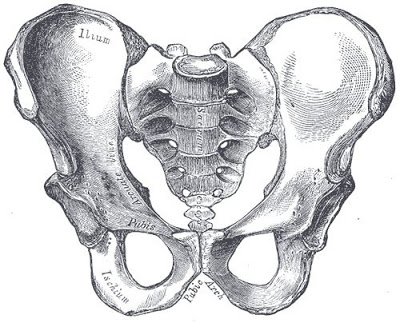

Finally, I consulted my physician who in turn referred me to an orthopedist. After a thorough physical examination and a demonstration of the pose at his request, he finally diagnosed my pain as being caused by inflammation of the sacroiliac joint (SI joint). He explained that the cardinal symptom of SI pain is an ache on or around the posterior superior iliac spine (PSIS), on one side of the body only (in my case it was the right side). The posterior superior iliac spine is the rear-most point of bone on the pelvis. It is easy to palpate it by pressing your fingers into the back of your pelvis above the main mass of the buttock, about two or three inches to the side of the center line of the upper sacrum. You will feel a distinct, bony prominence beneath your fingers. If a student tells you that spot or the depression just to the inside of it is achy or tender, while the corresponding spot on the other side of her body is not tender, then the student is probably experiencing an SI problem. However, my orthopedist clearly stated his inability to objectively measure the degree to which the SI joint was “out.” He suggested I take corticosteroids to bring down the pain and inflammation.

I am not a “pill” person and resolved to use the same environment where the SI misalignment occurred—my mat and the very yoga practice—to help strengthen the joint, sacrum, and hip. To do that, I had to first educate myself on the sacroiliac joint. The two SI joints are weight-bearing joints that distribute weight from the spine to the lower extremities (legs) through the hip joints. The SI joint is formed by two bones: the sacrum and the ilium.

The SI joint has only a small amount of movement and its major function is stability. This is needed to transfer the downward weight of standing and walking via the lower extremities. Held together by strong yet pliable anterior sacroiliac ligaments, the SI joint is designed to lock in place in standing positions with the sacrum bone wedging itself into the pelvic joint due to the weight of the trunk. This compact sacrum-pelvis connection together with the psoas and illiacus muscles creates a firm base for the entire spinal column. However, when you sit, this stability is lost because the sacrum is no longer wedged into the pelvis. The SI pain is a result of stress at the joint created by moving the pelvis and the sacrum in opposite directions. This can be caused by an accident or a sudden movement, as well as poor standing, sitting, and sleeping habits. In yoga asanas, inflammation and/or pain mainly arises due to the unusual and consistent stresses experienced by the supporting ligaments and muscles around the SI joint. This is especially true in asanas that move the pelvis and sacrum in opposite directions (twists or forward bends with legs wide apart as in Parivrtta Janu Sirsasana or Upasvista Konasana).

After knowing more about the importance of the SI joint, I returned to my yoga practice with caution. The SI joint remains healthier if it is not stretched too much. In fact, focusing on creating stability is the key to preventing SI joint overstretching and thus remaining pain free. I focused on strengthening the muscles around the SI joint by practicing simple backbends and standing poses. I began to take particular care with my pelvic alignment in twists and forward bends. I had aggravated the sacroiliac pain in large part by the way I was practicing seated twists and seated forward bends. While I was meticulously keeping my pelvis firmly on the floor during twists and seated forward bends, I allowed my spine to twist strongly in one direction, while my pelvis “strained and stayed behind.” While every pose needs an anchor, in twisting poses the anchor is not the pelvis; instead, it’s the thigh and the foot that is on the floor. The most important thing to remember about the SI joint is that it is a joint of stability and not mobility. In seated forward bending poses, such as Janu Sirsasana (Head-to-Knee Pose), Baddha Konasana (Bound Angle Pose), and Upavistha Konasana (Wide-Angle Seated Forward Bend), just sitting in and of itself “unlocks” the sacrum and the ilium. If additional stress is then placed on the joint, discomfort and/or injury could occur.

I remember discussing my issue with Baxter and he suggested that the only way to prevent further injury and discomfort is to meticulously move the pelvis and sacrum together. Based on Baxter’s suggestion, I paid attention to allow my pelvis to move with my spine, thus preventing the separation of the pelvis and sacroiliac joint by incorporating the following modifications:

- In poses seated poses like Janu Sirsasana I started practicing by placing the foot of the bent knee touching the opposite knee instead of the inner thigh to reduce the torque of my sacrum and ilium.

- To reduce the stress that the weight of the thighs places on the SI joint in seated poses, I started placing a firm, rolled blanket under my outer thighs especially in Baddha Konasana and Upavistha Konasana.

- Since bending forward from a seated position can add to the destabilization of the SI joint, I started bringing the legs closer together than usual and rest the arms and forehead on a block or a rolled blanket positioned between the legs.

- To prevent excessive stretching of the ligament, I held these poses for short periods. I also took extra care not to push down on my knees or place extra weight on them in order to increase the stretch.

- I focused on strengthening the SI joint area by doing simple backbends, such as Dhanurasana (Bow Pose), in which the pelvis moves forward and contracts the posterior muscles. This helps move the sacroiliac into place and also strengthens the muscles of the lower back and hip.

- I focused on standing poses as they help strengthen the area around the sacroiliac joint. Warrior poses, Trikonasana (Triangle Pose) and Utthita Parsvakonasana (Extended Side Angle Pose) strengthen the Iliopsoas and gluteal muscles that help to stabilize the area of the SI joint.

With all of the above modifications, I healed from the very place where I first damaged the SI joint—my mat—and am now completely pain free. Take home messages:

- In asanas, never create a torque of the sacrum and ilium moving apart.

- Understanding the importance of keeping the sacrum and pelvis together in twisting and sitting movements—is the key to remaining pain free.

- Healing the sacroiliac joint requires for the practitioner to be mindful of all the movements.

- The goal is to safely advance the strength and function of the SI joint.

Follow Yoga for Healthy Aging on Facebook ° To order Yoga for Healthy Aging: A Guide to Lifelong Well-Being, go to Amazon, Shambhala, Indie Bound or your local bookstore.

Good post!

Fantastic article! I've always felt one of the best gifts the west can bring asana practice is an extended knowledge of anatomy and modifications that come out of an understanding of alignment. We are all different but the same, and carry a lifetime of physical burden in our bodies. Therefore, understanding classic alignment as well as how to modify for our own bodies is incredibly important. I did the same for a massive shoulder/rotator cuff injury and was able to avoid surgery and recover nearly completely thru PT and my yoga practice. But it took me going back to square one and re-examining everything from scratch.

Thank you so much for this valuable information! I was wondering something about this in Baxter’s recent video demonstrating twists without arms. When we press down on the opposite hip to get a little deeper twist, could that irritate the SI? I haven’t experienced that but wondered if I should be aware if I have students with SI issues. Thanks.

Dear Andrea,

Thanks for your question. In the case of healthy students with stable SI joints, anchoring the opposite sitting bone done and extending up to the crown of the head will encourage axial extension (lengthening up the spine) which usually supports healthier twisting. In the case of those who are hyper flexible, or who have injured their SI joint, that instruction may or may not work as well. However, since I have been sharing that technique over the last several months, it has been generally well received. Another way to cue it would be to ground both sitting bones down equally and imagine initiating the twisting action from above the navel area. This usually leaves the pelvis and SI in a neutral alignment. Hope that helps! Baxter

Thank you for your very helpful response. I like your idea for the optional cue and will try that out, too. Namaste

As a pretty mobile dancer, I've had to learn about SI stabilization in order to avoid triggering pain and instability. I agree with everything in this post and would add that an awareness of the position of the femur in the hip socket is also important, especially in sitting poses with straight legs like dandasana, paschimottanasana, and upavishta konasana. It's critical that the head of the femur sits in the rear of the socket rather than pulling forward out of it in order not to strain the SI joint.

Thank you for this post. Excellent information. I'm wondering what you would advise about doing the figure 4/supine pigeon pose. Or even sitting cross-legged. Any recommendations?

Very good question.

Remember, asymmetrical poses like Pigeon places a very strong force on the sacroiliac joint (SI joint). In asymmetrical poses where one leg is stretched forward/backward and one leg is bent at the knee, the external rotators and abductors of the bent-leg side of the SI joint are stretched, while the stretched-leg side of the SI joint is being compressed. The stretched leg’s position requires for the neck of the femur to press into the anterior border of the hip socket. Incorrectly done, this can wear down on the hip socket and the cartilage on the head of the femur. Tightness in the external rotators and abductors can transfer into the knee of the bent leg, putting shearing pressure on the knee joint. Furthermore, in these asymmetrical poses, the pelvis is generally unsupported and so the weight of the entire torso further amplifies the burden on the SI joint. One way to rectify these problems and do the poses in a safe manner is to modify the poses and get the same benefits.

Just as you suggested, Supta Ardha Padmasana/Supta Kapotasana (Supine pigeon pose) and Padmasana (or modifications like sukhasana) help relieve tension in the external rotators and abductors. Note that in these poses, there is less of asymmetry in both legs and the action on the SI joint is much more symmetrical.